“Pattern recognition and understanding is …the whole of human scientific and artistic endeavor…the attempt to discover Pattern in Nature.“ Ian Alexander

We know our world is not random because predictable and consistent patterns exist naturally in the world around us and are evidence the world is not random. Patterns develop consistently and persistently according to the laws of nature.

We humans recognize natural patterns and create patterns of our own for our human world – language, numbers, art, music, society, buildings, religion, sports, and well…just about everything.

Patterns have properties. Most we can see or experience in order to learn more about our surroundings. Understanding this knowledge makes us better designers and builders and crafts persons. In recognizing patterns I’ve assembled my own list of properties for patterns. Usually, patterns inherently have only a few properties on the list, and the combination of properties for each pattern makes each one unique.

Below is my list of properties of patterns; your list will probably be different. In dissecting my interest in patterns, my list of properties below was helpful as my focus for not only studying, but really seeing patterns.

- Shape and Line

- Consistency

- Repetition

- Symmetry

- Color

- Texture

- Contrast

- Detectability

- Functionality

- Connectivity

- Organization

- Similarity

Symbolic Shapes

The most important shapes in our communications are symbolic shapes – simple shapes recognized and understood by all – made with simple lines. Symbolic shapes, quickly drawn, require less artistic skill to draw than realistic artwork. Our lines within the shapes – straight, curved, long, or short – are inseparable from the shapes in our images.

Meet my family – daughter, me, wife, son. The picture doesn’t do us justice; we are healthier than this. My rough line sketch is recognizable as a family, even though symbols are used for body parts – standard stick figure lines for torsos, legs, and arms, and a crude circle head. I gave each person a mouth, nose, and eyes, but males get ears and no hair. Females get hair but no ears. The family members hold hands as a symbol of “family”.

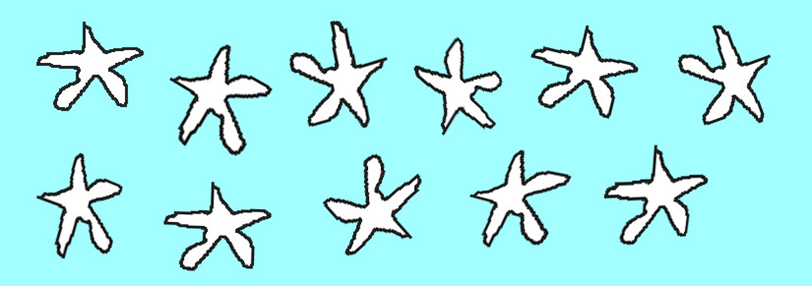

If we asked a young child to draw a group – of say, starfish – using only lines and shapes, would she draw a group of starfish using symbolic shapes? We expect that since a five-pointed star shape is easily recognized internationally symbolically and is easy to draw. However, we must remember it is only a symbol. Our five-pointed symbolic star shape looks so different from stars in the sky, it’s mysterious why we relate it to distant dots of light from real stars. Star symbolism is now ingrained; symbolic stars are displayed on flags and commercial signs and used in naming starfish and starfruit. We all recognize the “stars” in them.

Most would expect her sketch to look like Image 3. Each starfish sketched has a stylized, symbolic shape drawn by her. The symbolic shapes drawn create a mental image of starfish, and if she had drawn this, we would acknowledge it is a reasonable sketch per our request.

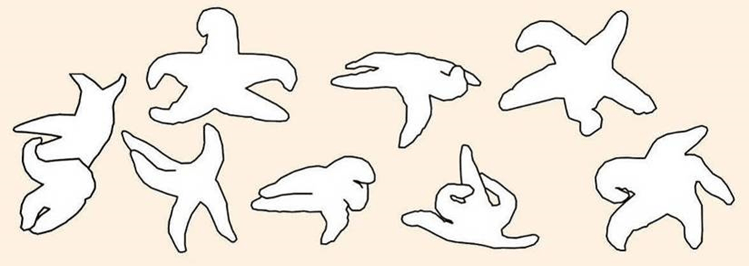

But she’s a budding artist and did not want to draw star symbols to represent living starfish. Instead, she traced starfish outlines she photographed the day earlier at the beach. Her resulting sketch is a group of contorted starfish (Image 4). And having expected symbolic star shapes, these images are not readily recognized as starfish. We may consider her oddly shaped starfish to be poorly drawn. Maybe they were…or maybe she’s an artistic genius drawing her own impression of Picasso-like starfish.

The starfish shapes and lines alone had too little detail. Additional pattern qualities – such as color and texture – were needed to make her images recognizable. Adding orange or purple color with small white, bumpy dots will make all the distorted shapes consistent and similar. Adding context – surrounding tide pools and rocks – will further clarify the contorted shapes. It takes time and skills to adequately show color, texture, and context quickly to change a sketch from symbolic to realistic. Fortunately, her photos (Image 5) have sufficient pattern qualities – line, shape, color, texture, and context – to show us her contorted shapes were accurate drawings of starfish outlines.

Recognizable symbolic shapes such as five-pointed stars, using only line and shape, are powerful for communication. Yet, if they are not recognizable symbolic shapes representing the real thing, people are confused.

In another use of symbolic shapes, our family has developed quick symbolic sketching systems for playing “Picture Dictionary”. Players focused on symbolic shapes, using only lines and shapes, usually win. Losers draw too much detail; quick interpretation of symbols and their meanings are more important than drawing ability.

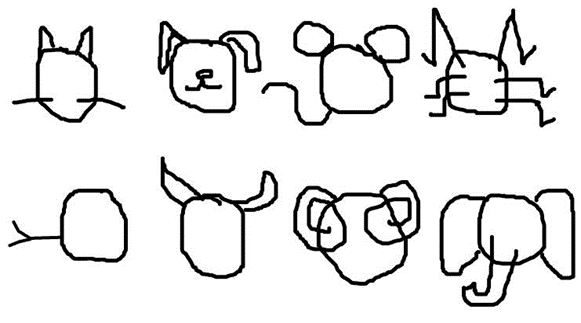

The quick symbolic sketching system works like this. First, a circle with body parts attached indicates “an animal” (Image 6). A 4-legged creature has no legs attached; an insect has 6 legs attached; 2 legs are for humans. To give another clue, well-known animal parts are attached to the circle. Below, in no order, are a grasshopper, sheep, dog, cow, snake, elephant, cat, and mouse.

If the first sketch is not correctly guessed quickly, the sketching player crosses it out and starts a second one beside it (Image 7). The second sketch shows another part of the same animal. Both sketches usually apply. The answer is a cow – the first sketch has horns, the second one has an udder (which could have been connected directly to the circle).

Quick, recognizable, symbolic shapes with only a few lines usually win.

Cartoons and Line Drawings

Simple line cartoons, which are used similarly to symbolic shapes, are often included in planning meeting presentations to quickly show concepts. The sketched cartoon in Image 8 illustrates a technical concept to a multi-discipline team of designers; the wild, articulated exterior façade – a dancing woman – on one side needs a more heavy, stable partner so the whole building has stability to match the wild facade.

A diagram sketched quickly on a chalkboard (Image 9) is part of a football offensive option play. Lines and shapes as symbols are used for offensive/defensive players, movement during play, and blocking. It’s similar to patterns many recognize from high school playbooks.

Lines in Communications

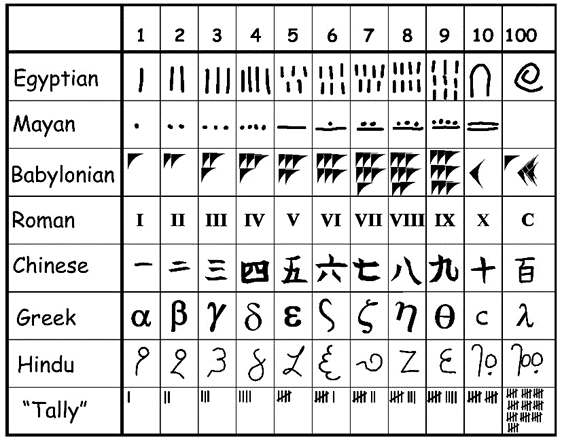

Written languages and numbers contain simple lines to create patterned shapes recognized by all who know the language or number systems depicted. Lines are simple to draw, teach, and learn. For instance, we count and keep tally scores for teams B and C (Image 10) with each line counted as a number “one”. Blocks of five lines make it easier to tally them. This is similar to how counts were notched into this old bone (Image 11), showing that patterns for tallying are not new.

To become recognizable symbols communicating modern numbers, letters, or words, lines are drawn or etched to different symbols. Each shaped symbol has meaning. Those in cultures who understand the symbols interpret them into words and numbers in their spoken languages. In doing so, our thoughts are communicated in spoken language between each other through writing. Writing can communicate ideas or numerical records by one person to millions of people – for millennia – using only recognizable shapes of lines.

Lines Bring Order

A boundary fence along a farm’s property line (Image 14) marks a division between privately-owned and publicly owned land. Boundary lines anywhere – property lines, country borders, and street rights-of-way – are legally defined in documents yet they are not visible unless the lines are surveyed and marked. Only humans recognize these imaginary lines, locate them, and give them high importance. Wild animals living in our neighborhood – slugs, birds, and squirrels – totally ignore property lines between us and neighbors.

When farmland is divided into fields (Image 15), farmers planting adjoining fields can plant each field in a different crop revealing the field’s boundary locations. A road along a field’s boundary also makes the invisible boundary lines physically evident.

Lines have vast power to bring order by creating recognizable patterns. Image 16 shows only a few additional ways that lines make patterns and bring order.

- Pathways, such as roads, trails, or tracks show the way to travel. A plane’s contrail shows where it’s been.

- The horizon yields a reference line for “horizontal”. It marks a universal boundary, which all use to help measure star locations, to navigate, to survey, or to tell time.

- Direction of the sun’s light rays can tell us compass directions – N, E, W, and S.

- The angle of the sun’s rays to the horizon can help tell the time of day or the season of the year.

- Fences on boundary lines bring order between us and the neighbors’ dogs.

- Lines define rules of play in sports.

- Hiking in a line, often roped together, maintains order and safety on a glacier climb.

- Lines (queues) form at entries to ballgames, theaters, and amusement parks; lines help keep order, politeness, and courtesy.

- Orderly planted in rows, neighboring vegetable types remain manageable for gardening.

- Lines in fingerprints help identify individuals through personally unique fingerprint patterns.

- Lasers reading lines in bar codes track items and their inventory and pricing.

2 Public domain

3 Paul Brennan from Pixabay

4 by freestocks-photos from Pixabay people-2943111_1920

Dice and Other Game Piece Shapes

Not all shapes are symbolic. Shapes for games and art are often generated by either nature’s patterns or geometry patterns.

Shapes in Image 17, made 20 years ago by a Tlingit Alaska Native, and in Image 18, made 150 years ago by Inuit, are unique to their respective cultures. Most of us would not know how to use these small items, which were hand carved by Native craftsmen from ivory, bone, or antler.

My son found the pieces in Image 17 while shopping in Southeast Alaska. But the pieces weren’t displayed for sale. Most tourists wanted “native looking” souvenirs and were willing to pay a nice sum for nicely crafted artwork of bone, antler, stone, or ivory. A handcrafted trinket piece did not interest him. My son, who worked for a Native American tribe, wanted a unique, simple, cultural souvenir that was personally handmade by a Tlingit tribal member. He asked shopkeepers for personal objects made by any local Tlingit artist, simple ones not made unrealistically “nice” for tourists. After not seeing what he sought, he asked the question in a different way. He asked if any Tlingit made things for their children which were not for sale to tourists.

It was the right question. One Tlingit shopkeeper pulled out a leather bag, opened it, and poured out polished pieces (Image 17) for my son. “I’m not a gallery artist, but I get bone and antler scraps from their workshop. I made these traditional game pieces for my kids, and I’ll sell them to you.”

Highly polished bits of antler and bone lightly bounced as my son rolled them out similar to dice. Unlike dice, however, they were non-geometric, irregular, and unique. Bartering for a decent price, he bought the set.

This simple game, an adaptation of an older game, had 14 pieces. Each piece had a flat side, where it was cut from bone or antler. To play, a player first rolled all pieces out. Pieces landing with flat sides down were moved aside and the remaining pieces rolled out. Again, pieces landing flat side down were put aside and remaining pieces were thrown again. This was repeated until no pieces remained to throw. A player’s turn was scored by how many throws were needed until all pieces landed flat side down. Players took alternate turns and the player with the lowest total number of throws won.

Inuit played a similar game but used carved ivory geese for pieces (Image 18). Players dropped or tossed the ivory birds onto a flat surface; players keep ones that land upright. The game progresses with players tossing or dropping birds to see which birds land upright.

Geometrically Shaped Dice

There’s a big difference in shape between naturally shaped Alaska Native game pieces and our modern geometrically shaped dice of European-Middle Eastern origins. Our modern plastic, geometric dice (Image 19) are based on invented, idealized, geometric shapes, not connected to natural shapes.

Regular Platonic solids (Image 20) and their variations are commonly used for modern western dice bought from toy and game manufacturers. Drawings of five Platonic solids by Leonardo DaVinci appeared in the De Divina Proportione in 1509, by Paccioli – tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron, and icosahedron. Also called regular solids, these five solids are formed by joining identical, equilateral, equiangular polygons together into a solid, without gaps between the polygon sides. Each vertex point has the same number of polygonal sides meeting together at the same angles.

Image 20 shows the Platonic solids: Tetrahedron with 4 triangles, Cube with 6 squares, Octahedron with 8 triangles, Dodecahedron with 12 pentagons, Icosahedron with 20 triangles.

To visualize the polygons in Platonic Solids, they can be drawn flattened on a pattern on paper. The polygons are connected and arranged so if cut out and folded, a Platonic shape is formed by joining (and taping) sides of polygons together. Image 21 shows flattened patterns drawn (left to right) for a tetrahedron, a cube, and dodecahedron, from which corresponding solid shapes can be made.

Platonic Solids are unique geometric shapes, but why use the shapes for dice?

An answer lies in the needs of a game. The best die shape in a game will have an equal chance of landing on any given side of the die. With each side of a Platonic solid having the same shape, and each side vertex intersecting at equal angles, the Platonic solid’s center of gravity is equidistance from any of its vertices or from any side. These shapes are the best we can do in getting equal chances for each throw.

Like Tlingit and Inuit game pieces, shapes in traditional Northwest Coast Native woodcarvings and paintings are based on natural shapes, not European-Middle Eastern geometric shapes. The shapes used commonly in Northwest Coast art are well-known, historical shapes. The common artistic shapes used have recognizable forms and names.

Below, in Image 22, are some shapes common to Northwest Coast Native art: ovoid, circle, trigon, U-form, crescent, split-U-form and S-form. Ovoid and U-form shapes of various size and thickness comprise major design elements in an artwork. Trigons, crescents and circles in relief make heavy lines and large solid elements in carvings, while S-form and other fine line forms fill spaces and fluidly connect major elements.

Names of the shapes used in Northwest Coast Art remind artists of their natural origins. The Haida word for “split-U-form” also means “flicker feather”, since a red-shafted flicker’s tail feather, Image 23 top, makes this shape when placed inside a U-form. The Haida word for “ovoid” also means the similarly shaped spots on the Big Skate, Image 23 bottom.

Shape and shape recognition are important within the beautifully formalized content of Northwest Coast art, since native carving, painting, or weaving traditionally contains recognizable, yet stylized, animal shapes in a style symbolizing family relationship and stories. Although the artists flexibly and freely adjust symbolic crest shapes to suit their carved layout and form, the natural forms are recognizable.

Road Signs and Urban Icons

We have modern cultural shapes, too. Often based on geometric shapes, traffic signs occur throughout the world. Similar to each face of our dice, geometric shapes – squares, rectangles, triangles, circles, diamonds, hexagons, and octagons – are universally recognizable in traffic signs, sometimes making them visible before we read them. Their shapes, color, and context all relay the signs’ messages to us quickly. Some familiar geometrically shaped signs with graphic shapes painted on them are shown in Image 24 (below). They reside near roads in different countries; their message is communicated not only by sign shape and painted shapes, but also by text and color.

Traffic signs are not the only “icons” we see planted on our landscapes. Although not simple geometric shapes or solids, these icons in Image 25 (below) dot our environment. Their distinctive shape and color often are a warning or an offering to drivers or pedestrians. Iconic shapes often greet us as we reach an intersection, seek to mail a letter, or need to douse a house fire.

Icon images are from the U.S.A., Canada, Israel, and the Philippines; their shapes, together with colors, are symbolic of their purpose. Hopefully we recognize and understand not to drive over a tire-puncturing device embedded in the road if we are entering a restricted area using the wrong opening – the exit. And we drive cautiously around a group of traffic cones, stop for a parking entry gate, walk over sidewalk grating, and walk under scaffolding above the sidewalk.

My photo collections of symbols, trademarks, cartoons, games, geometrical shapes, numbers, languages, cultural art, road signs, and urban “icons” are all part of my passion for patterns. The images remind me that so many patterns of objects surround us every day, yet they go largely unnoticed. I remind myself that someone or some group designed each one of these items and decided how shape and line, as well as other properties of patterns was used in their design to convey their message or their purpose.

Leave a comment